Further to the images on the last blog entry, below are my final five chosen photographs, with borders and names.

Medium format portraits inspired by August Sander

Having been inspired by the ambitious project of August Sander to document the whole of society in Weimar Germany in the early 20th century, I launched my own mini project to document some of our older citizens here in the United Kingdom.

The brief I set myself was to picture each person located in the place they feel the most comfortable with the item they treasure the most. Interestingly each of them chose to be in their gardens. I found this interesting in terms of the British psyche – perhaps because by nature British people can be quite insular and reserved, the place they like the most is often somewhere they feel free.

I also used August Sander’s tactic of showing his subjects with an item that tells their story – with him it was mostly picturing people with tools of their trade. For me, I wanted to picture people with something that they identify with and which has great sentimental value to them.

Here are my portraits, taken on a medium format Pentax camera. I have also included test shots and contact sheets.

Losing control of ‘his’ people… August Sander after the war

I find it a terrible pity that August Sander’s work was cut short by the advent of war in 1930s Germany. And for so many of his negatives and photographic plates to be subsequently destroyed either deliberately or as a result of bombing raids is an even greater pity.

It always feels wrong when any kind of art is destroyed because someone else is either threatened by or doesn’t like it. Art is an expression of the soul and it can survive long after the artist has made it, and can tell us so much about a particular period in history or about the psyche of the artist.

I feel that August Sander, by the time war was over in 1945, was beginning to tire and feel that the world that he had been documenting had changed too much. By 1945, he was nearly 70 years old, he had recently lost his son to the Nazis and much of his work had been destroyed. In addition, many of the archetypes that he had photographed for his Faces of our Time were no more. In the place of the young farmers, we see young people starting to get into rock ‘n’ roll music. In the place of the middle-class mother, the career woman. As historian Beaumont Newhall wrote in his History of Art: “That the world had changed since the conception of the project can hardly have missed Sander’s notice. Where youthful gestures of protest might express themselves in 1914 through cigarettes and a hat askew, the world after 1945 sported chewing gum, rock and roll, jeans, and petticoats as signs of the modern spirit. In a certain sense, August Sander had lost hold of ‘his’ people.”

It should be noted that he still contributed a lot of valuable photographic work between 1945 and his death in 1964, but I think he realised that the likelihood of completing his life’s ambition was ebbing away. A sad but true fact. Nevertheless, the portraiture he was able to leave to us has, without a doubt, shaped modern portrait photography and also allows us to reminisce about life in a pre-Nazi Germany between the wars; a Germany that was lost forever after 1939.

Following August Sander’s example

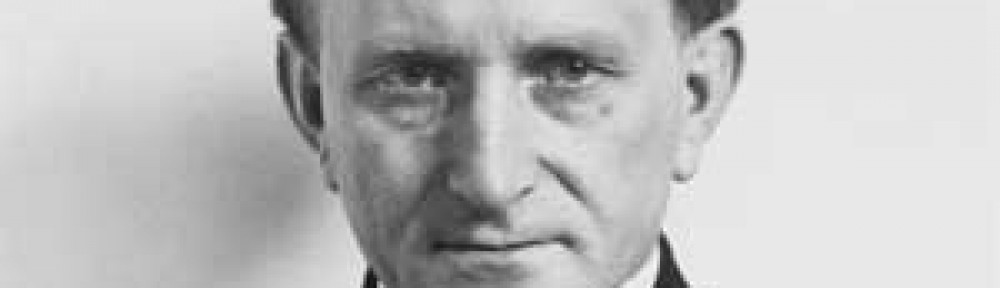

I know it might sound a little odd, but for the past month, I have kept a small self portrait of August Sander in my pocket. I was informed that doing this would help me to get closer to the real identity of who August Sander is and remind me of his practices and techniques when undertaking my own photographic portrait work.

I know, obviously, about Sander’s preoccupation with portrait photography, but what else did I need to bear in mind when attempting to ‘follow’ his work?

- his portraits emphasise contrast, with sharp delineation between dark and light and strong mid-tones of grey

- he varied the depth of field in his photography, depending on his subjects and their location

- he more often than not used large format cameras. His favourite was known to be the Plaubel plate camera with Zeiss lenses and orthochromatic plates with light filter

- because of his predilection for large format photography, his attention to detail was very clear in his photography. Small details, like the watch on the wrist of one of the girls in Country Girls, are much clearer than if he had used a different sort of camera.

I have recently been experimenting with medium format photography, so I have decided to use a medium format camera in order to capture as much detail as I can in my shots, shooting on 120 film with a Pentax medium format camera.

I have also concentrated on portraiture, and, as Sander encouraged his subjects to carry the tools of their trade, I have asked my subjects to hold something that is dear to them. See a later blog entry for some examples of my work ‘following’ August Sander.

August Sander and documentary photography

Documentary photography has come into its own over the last 20 to 30 years, with photographers like Garry Winogrand and Philip Lorca DiCorcia making the everyday into real works of art with universal appeal.

But in the time of August Sander, at the turn of the 19th to 20th century and in the 30 to 40 years afterwards, documentary photography was rarely to be found. Although his portraits still had a certain static nature to them and a staged feeling, in my opinion they provided the roots of the documentary photography style that we see today.

Talking about the value of photography as documentary evidence of historical fact, the historian Beaumont Newhall said: “the photograph has special value as evidence or proof”. I think that is the key benefit of much of Sander’s work; it has, as he wanted it to, stopped the world still at the moment he took those pictures. We live in 2011, in a fast-paced scientific modern world, but his images capture for us a 1920s coal carrier, a bricklayer from the same period, or a farmer from turn of the century Germany. In that way, if nothing else, he has performed a vitally important documentary task.

And it has given the opportunity, as referred to in ‘Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices’, to the people in Sander’s pictures to communicate with modern viewers. As he writes: “through the photographer’s construction of their existence at a given moment of time and space, subjects who have no opportunity to speak directly to people outside their immediate area are provided with the chance of ‘giving testimony’ to the readers of a newspaper or magazine”.

Research: Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (Sage Publications Limited, 1997, pp. 81-87), edited by Stuart Hall

Were all of August Sander’s portraits genuine?

Writing in Source magazine in 1997 (Sander’s work was at the time being exhibited at the Photography Gallery in Dublin), reviewer Stephen Bull raised the question of whether all of August Sander’s work was as genuine as it was portrayed.

He commented: “Perhaps there is something suspicious too about those folks depicted in the principal mass of Sander’s project. Many of them could almost be character actors trying out roles for their portfolio. The ‘Trade-Unionist’, sleeves rolled up to his elbows, poses dramatically in front of a white backdrop. Others display basic props; a ‘Postman for registered mail’ pretends to fill in a form: an ‘Unemployed man’ waits, cap in hand, a’Barrister’ holds up his papers. Rarely do we see these people actually acting out their roles. There is a peculiarly static concordance to the nation we are shown. Everyone has their part to play, from beggars to bankers. Even a group of revolutionaries are absorbed into the harmonic structure that Sander imposes. It is as if this is the way the world always was and how it will always be; a society as rigid as the poses of the men and women who make it up.”

This did make me start to think. Could it possibly be that I had been ‘duped’ by the father of modern portrait photography?

It is certainly true that many of Sander’s works come across as fairly static and, sometime, almost too obvious. However, examples like pictures of opera singers or politicians, who were clearly known at the time help to emphasise Sander’s professionalism. Would someone who is clearly professional and who has consummate skill with a lens allow their integrity to be called into question by ‘faking’ their portraits? Their life’s work?

In my opinion, the answer is probably no. Sander strikes me as a hard worker, someone who did not mind pushing themselves to achieve a goal. As his life’s goal was to complete his Faces of our Time project, I don’t believe he would ‘cut corners’ to do it. The truth may be more to do with Sander’s previously stated aim of ‘holding fast the history of the world’.

As Bull continues in his review for Source, perhaps Sander actually did this project to push against the changing world of Weimar Germany. He wanted to retain the old order, the old structure of things. Referencing the psychologist Freud, he writes: “…it may be partly understood in terms of Freud’s idea of the uncanny. The word translates into the German unheimlich, itself derived from heimlich, or homely. One of the aspects of the uncanny, Freud contends, is anxiety produced by the unknown, the changing, the new. August Sander’s impossible mission could stem from a desire to apply the familiar genre of portraiture to the new and evolving medium of photography. This, in turn, is used to create a comfortable, homely society, instead of an unheimlich nation in a state of flux.”

Research: http://www.source.ie/issues/issues0120/issue12/is12revaugsan.html

What did August Sander contribute to modern portrait photography?

August Sander is often seen as the father of modern portrait photography and certainly, since the end of World War II, the level of interest in Sander has been growing exponentially. Looking again at some of his work from the period 1910 to 1930, it is clear that this was an artist ahead of his time, out of place almost in the maelstrom of emotion swirling around Weimar Germany following the end of World War I.

His work has echoes of the modern snapshot, but in a world when the ‘snapshot’ was still to evolve.

However, deeper research into his work and into his psyche show that his aim was very different to that of the modern snapshot. He had an entrenched belief that society was divided into occupational hierarchies and it was his aim to capture for posterity those hierarchies in a way in which they could always be recognised. For example, with tradesmen, he pictured them with the tools of their trade, with people who had disabilities he made sure he photographed them clearly delineating their disability and naming the pictures as such.

In his 1929 publication of Faces of our Time, a collection of sixty photographs of people from different strata of German society, he divided the book into several different categories: The Farmer; Classes and Professions; The Woman; The Artist; The City; The Last People. The Last People captured, as Sander himself called them, the “idiots, the sick, the insane, and the dying.” In a way, this publication for Sander captured the cycle of life where the dying return to the earth and the cycle begins again with the farmer, who tends the earth.

Sander also had a very simple approach to portrait photography, and a desire for documentation. Most of his portraits involved his subjects looking straight at the camera in an almost nonchalant way, like they were on their way somewhere and simply asked to stop and look at the camera, the tools of their trade or their distinctive clothing marking them out as holding their position in society.

So what did he contribute to modern portrait photography? I feel that what he contributed was the belief that everyone is entitled to be documented. In the early days of photography it was the aristocracy, the monied classes who could afford to have their portraits taken. Sander helped to usher in the age of mass photography appreciation. His work also helped to inform the beginnings of street or documentary photography.

- The Woman – Architect’s Wife, 1931

- The Last People – Blind Children, 1930

- The City – Bohemian, 1922

- The Farmer – Farmer from the Westerwald, 1910

- Classes and Professions – Member of Parliament (Democrat), 1928

- The Artist – Sculptress, 1929

Some of August Sander’s famous portraits

August Sander, the German 20th century photographer, had a declared aim to ‘hold fast the history of the world’. He wanted to stop time, construct his own world and preserve it through his photographs. He did this by creating a large series of portraits (which he intended to be larger until that was stopped by the Nazis) trying to capture images of every level of German Weimar society during the inter-war years (most of his images for this project were taken between 1918 and 1936).

I will talk more about his approach elsewhere in this blog, but before I take you further, this entry will show a selection of his portraits along with their names (which he simply titled with their profession or vocation and the year in which he took the photograph)…

- Blind children, 1930

- Bricklayer, 1928

- Circus artist, 1926

- Circus workers, 1926

- Country girls, 1925

- Herbalist, 1929

- High school graduate, 1926

- Notary, 1924

- Travelling carpenters, Hamburg, 1928

- Young soldier, Westerwald, 1945

Introducing August Sander – a short biography

August Sander was a German photographer known as the ‘father of modern portrait photography’. The more I have studied his work, the more I have realised that the work he pioneered really has shaped modern photography in so many ways.